The women in mycology played a crucial, yet too often overlooked, role in establishing the field during the Victorian period. Their dedicated research, documentation, and scientific illustration produced some of the most important texts in the study, works that were pioneering both academically and creatively.

The mid-nineteenth century was a period of rapid transformation in the natural sciences, and the little-understood world of fungi offered new ground for speculation and discovery. As a woman at this time, it was nearly impossible to be recognised as a legitimate scientist, with the Victorian scientific establishment being notoriously hostile to female contributors, leading to a period of little credit for many working in the field.

While the study of botany was a culturally approved discipline for women from the Enlightenment era onwards, they were often excluded from formal training and professional networks, remaining uncredited for any contributions. However, that did not stop them from making some of the most groundbreaking and beautifully illustrated contributions in the field.

Discover a list of the key women in mycology, whose significant contributions helped establish mycology as its own branch of science. Their achievements leave behind an inspiring legacy for women in mycology, as well as an invaluable archive of fungal taxonomy in the formative years of mycological study.

Britain's First Female Mycologist

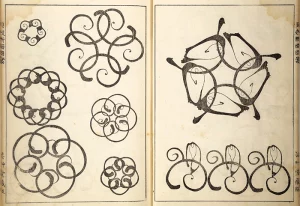

Anna Maria Hussey, often regarded as Britain’s first female mycologist, authored Illustrations of British Mycology (1847–1855), a pioneering two-volume work beautifully blending art and science. Co-illustrated by her sister Frances Reed, the collection features detailed fungal illustrations and scientific observations that established female-led mycological study in Britain. Her groundbreaking work influenced many future contemporaries despite receiving little formal recognition at the time. Her legacy endures as a foundational figure in early British mycology, later honoured by Berkeley with a fungal genus bearing her name. Often overlooked and seldom credited, Hussey’s legacy as a pioneering woman in early mycology endures through her publication & contributions to the field, staging her as a revolutionary voice in the history of natural science and a leading woman in mycology.

An extraordinary record of British fungi and female scientific achievement, this volume showcases the pioneering work of Anna Maria Hussey and her visionary approach to art and mycology.

The Toadstool Lady of Maryland

Working largely unrecognised in her lifetime, Mary Elizabeth Banning (1822–1903) was a self-taught naturalist whose remarkable The Fungi of Maryland (1888) stands as the first illustrated study of American fungi. Denied access to formal scientific circles, Banning nonetheless undertook decades of solitary fieldwork, identifying and documenting over 20 fungal species with meticulous precision and artistry. Unable to gain funding for her research, she became active and resourceful in her endeavours, gaining a reputation as a misunderstood ‘toadstool lady’—a title that somewhat diminishes the importance of her work. Her long correspondence with renowned mycologist Charles Horton Peck yielded mutual discoveries—Peck would later name a species in her honour, Hypomyces banningiae. Containing 175 watercolours and detailed descriptions, her manuscript was quietly consigned to a museum drawer upon her death, only to be rediscovered a century later. Today, Banning is rightly celebrated as Maryland’s foremost mycologist of the 19th century, her legacy a testament to perseverance, curiosity, and overlooked brilliance.

Rambles in Search of Flowerless Plants

Margaret Plues (c.1830–1903) was a prolific Victorian natural history writer whose popular works—Rambles in Search of Flowerless Plants (1861) and A Selection of Eatable Funguses of Great Britain (1866), among others—sought to make the study of botany and mycology accessible to a broad readership. Born in Ripon, Yorkshire, into a large clerical family, Plues remained unmarried and spent much of her life moving between relatives’ homes while working as a governess and author. In 1866, she converted to Catholicism and became a Franciscan Tertiary, later devoting herself to social work in London, where she managed a charitable home for converts. Plues spent her final years in Weybridge, Surrey, entering a convent before her death. Her legacy rests in a body of botanical writing that blended accessible science with a deep personal reverence for the natural world.

Fungi Collected in Shropshire and other Neighbourhoods

One of the many pioneering women in mycology, M. F. Lewis’s Fungi Collected in Shropshire and other Neighbourhoods is a quietly remarkable, though long-unpublished, contribution to British mycology. Spanning three volumes and over 200 species, Lewis’s manuscript pairs delicate watercolours with field observations of fungi from a region largely overlooked by scientific record. Working without formal education or institutional support, she devoted her life to cataloguing local fungal life with care and artistic finesse. Though known to learned societies of the time, her work remained unpublished and overlooked for over a century—now recognised as one of the most beautiful and dedicated mycological records of the nineteenth century.

On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricineae

Best known today for her beloved children’s books, Helen Beatrix Potter (1866–1943) was also a passionate and pioneering mycologist whose scientific contributions remain largely obscured. In the late 1890s, Potter made significant discoveries in fungal reproduction, producing detailed illustrations and a paper, On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricineae (1897), which was submitted, though not by her, to the Linnean Society. As a woman in mycology, she was barred from presenting her own work due to her gender, and as it was ultimately unpublished, the paper has since been lost. One of many women in mycology who was overlooked in her time, Potter’s early work in mycology reveals a brilliant scientific mind curtailed by the limitations of her era.

The works discussed here are but a few examples of the pioneering efforts made by women in mycology throughout the nineteenth century. Their efforts reflect a broader movement that connected art and scientific study across the emerging natural sciences, propelled forward by women working quietly in the margins.

The contributions of women such as Hussey, Banning, Lewis, and Potter reveal a parallel lineage of inquiry—one marked by exclusion, perseverance, and innovation. Bringing a unique perspective to the field, their illustrated works are an invaluable archive of fungal taxonomy in the formative years of mycological study. The research of these women in mycology transcended the limitations of their era, helping establish mycology as an independent scientific field, enriching the historical, artistic, and scientific records for years to come.