By the time Anna Maria Hussey’s seminal publication, Illustrations of British Mycology, was published between 1847 and 55, the history of mushroom illustration had undergone a profound transformation.

Taken from a feature in the Mycologia Journal on the subject of mycological illustration, this passage by Louis Krieger (1873-1940) explores the landscape of mushroom illustration as it developed from the fifteenth century onwards, up until the publication of Hussey’s Illustrations of British Mycology in 1847.

Published in 1922, Krieger’s essay pre-dates contemporary colour printing techniques, offering insight into the world when artisan techniques like lithography were considered cutting-edge in scientific documentation.

An extraordinary record of British fungi and female scientific achievement, this volume showcases the pioneering work of Anna Maria Hussey and her visionary approach to art and mycology.

A Sketch of the History of Mycological Illustration

Every taxonomist will admit that illustrations are essential for the identification of many plants, and especially in the case of the fleshy, perishable fungi. To be really serviceable, however, a picture must be truthful. This seems self-evident, yet, if we make a survey of the available mycological illustrations from the earliest times, we find that this quality of truthfulness was slow to develop. One of the causes of this is to be found in the freedom of the illustrator in following their imagination and another in the technical difficulties.

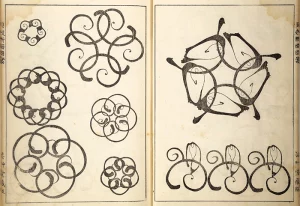

The first period, that in which wood-engraving was the chief means of illustrating, embraces the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The wood-engraving, practiced by the artists of the herbalists was, as already indicated, a crude, black-line engraving. An outline-drawing was transferred to the smooth wood-block. With sharp instruments the surface was cut away everywhere except under the lines of drawing. When completed, the block was held for printing as if it were type. In a more complex, shade-rendering form, in which white-and black-line engraving are intermingled, this ancient and most serviceable art persisted until displaced by the modern half-tone, sometime in the early nineties of the last century.

The second period, in which steel-and copper-engraving played the principal role in mycological book-illustration, began late in the seventeenth century and lasted until well into the nineteenth. In method of procedure it resembled the white-line engraving of the wood-engravers. The highly polished metal plate was cut into with suitable instruments to raise what is technically known as a burr. This burr retained the ink for printing after the surface of the plate had been wiped clean.

The third period, the lithographic period, began at first with black-and-white printing, the colour being added by hand as had previously been done with engravings. It was not long before lithographers printed in colours. This accomplished, the way was clear for a satisfactory, as well as a more rapid, printing of fungus pictures in their natural colours, the degree of excellence depending upon the artist who made the original paintings, and upon the lithographer who transferred the pictures to stone.

The other processes commonly used today in the reproduction of drawings and photographs, the zinc and copper line-engraving, the half-tone and the heliogravure,[1] need not detain us as all are familiar with the results. Of the two processes, however, the half-tone and the heliogravure, the former is much the less durable, for the reason that chalk-coated paper is usually the surface for the print. The mesh, present in all half-tone reproductions, may also be urged as an objectionable feature when a hand-lens examination for morphological details becomes desirable.

The very early herbalists paid little attention to the fungi, merely repeating what we find the ancient Greek and Roman writers, Theophrastus, Nikander, Pliny, Galen, and the rest. The earliest published illustrations of fungi that serve us today with any degree of satisfaction in the matter of generic and, in many cases, of specific determination are unquestionably those of Charles de l’Ecluse (Carolus Clusius) (1526–1609) published by him in 1601 in his work on They are uncoloured wood-cuts, rather clumsily done, but, for all that, sufficiently well characterised where common well-known species are shown.

[1] A printing process that transfers an image from a photograph to a plate and then onto paper.

In the eighteenth century things began to brighten. In 1729 appeared the work of the great Italian, Pier Antonio Micheli, who was the first to point out definitely that fungi have reproductive bodies or spores. With the exception of Robert Hooke’s (1635–1703) drawing of the teleutospore of a Phragmidium (1665) and Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli’s (1658–1730) demonstration of the origin of fungi from mycelia (1714), there is little in the literature before Micheli to indicate that fungi were anything more than freaks of nature produced by spontaneous generation or by thunderbolts, spooks, and the like. Micheli’s epoch-making Nova (1729) changed the views of mycologists forever.

In Germany, during the years 1762 and 1774, Jacob Christian Schaeffer was issuing that milestone of illustrative mycology, his The plates (hand-coloured copper-engravings) are not particularly good, but important as one of the original sources for the figures of many well-known species.

A veritable flood of illustrated mycological works was let loose from then on. In France, from 1786 to 1798, we have Pierre Bulliard’s colossal with 602 admirably executed, colour-printed engravings; and Paulet’s Traité des Champignons (1793). Sowerby, in England, was publishing, from 1795 to 1815, the Coloured Figures of English Fungi which, with Greville’s later Scottish Cryptogamic Flora (1823), represents the best that Britain had produced in the line of fungus illustrations.

With the dawn of the nineteenth century—in 1801—systematic mycology had its real beginning. England, during this period, had a women mycologist, Mrs T. J. Hussey, who presented to the world one of the most charming mushroom books known, her Illustrations of British Mycology (1847).

Within the timeline of mushroom illustrations, styles evolved from crude woodcuts to sophisticated lithographs that realistically depicted fungal forms. Hussey’s work (co-illustrated by her sister, Frances Reed) emerged as a landmark achievement in the world of scientific illustration. In a series of highly detailed lithographic plates, she united scientific accuracy with artistic brilliance, setting the stage for female-led mycological observation, spurring further publications enriched by artfully detailed mushroom illustrations.