Jane Colden (1724–1766) is now recognised as America’s first woman botanist. Her meticulous documentation of native North American flora stands as the earliest known record of its kind produced by a woman, as well as one of the earliest to employ Carl Linnaeus’s new system of classification.

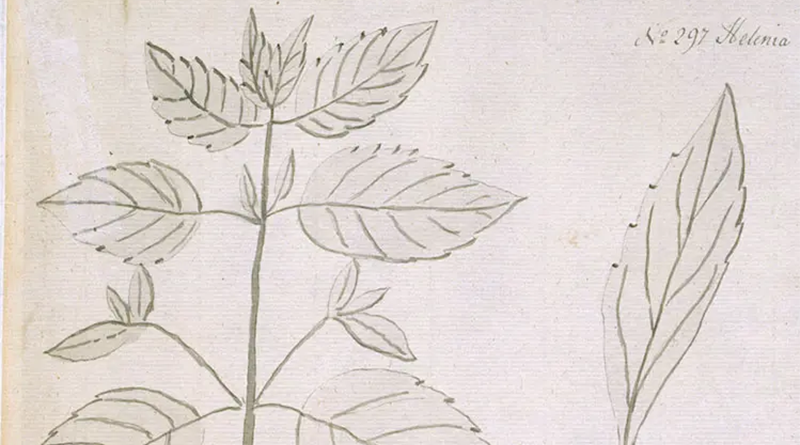

Her beautiful, yet unpublished original manuscript, The Flora of New York (produced between 1753 and 1758), remains a pioneering contribution to eighteenth-century botany.

Who was jane colden

Born in 1724 in colonial New York, Colden spent much of her life in the Hudson Valley on her family’s vast estate, Coldengham. Under the guidance of her father, Cadwallader Colden (1688–1776), she developed a sustained interest in natural history and the emerging Linnaean framework. Over the following decade, she compiled a detailed catalogue of more than 400 plant species found on her family’s land, producing a volume of work that would later be recognised as a foundational record of the flora of New York.

The mid-eighteenth century marked a turning point in the study of plants, as Carl Linnaeus’s revolutionary system of classification transformed botany from a descriptive art into a structured science. His Genera Plantarum (1737) and Species Plantarum (1753) introduced the binomial naming system and the “sexual” method of classification based on stamens and pistils—tools that gave naturalists a new common language for studying nature.

Within this emerging global network, Jane Colden became one of Linnaeus’s earliest and most remarkable followers. She adopted the Linnaean method to document and describe hundreds of native plants, her fluency in the new system earning her recognition among European botanists and a place—though often mistakenly attributed—in Linnaeus’s own botanical legacy.

It’s mistakenly recorded here that Linnaeus named the Coldenia genus after Jane, but it was in fact named after her father, a credited botanist in his own right.

The flora of new york

Although Jane worked in her own, private corner of the world, news of her botanical knowledge and discoveries was shared in the prolific letters of her father. Cadwallader promoted Jane’s fluency in the new Linnaean system, boasting of her success to his own (and highly esteemed) network of botanists around the world.

Through this network—corresponding with eminent naturalists such as Johannes Fredericus Gronovius (1686–1762) and John Bartram (1699–1777)—Jane’s observations reached an international audience, establishing her position as the first woman botanist in America to work within the new Linnaean framework.

“I have a daughter, who has an (natural) inclination to reading & a curiosity for natural philosophy or natural history, and a sufficient capacity for attaining a competent knowledge. I took the pains to explain Linnaeus’s System (for her), and to put it in English for her use by freeing it from the technical terms, which was easily done by using two or three words in place of one. She has now grown very fond of the study, and has made such progress in it that as I believe would please you if you saw her performance.”

—Section of a letter from Cadwallader Golden to Gronovius,

New York Oct. 1st, 1755.

Botanical illustrations and nature printing

Her work combined acute observational skill with a scientific understanding of botanical structure and function. Furthering her scientific enquiry, she conducted experiments on plant reproduction and cross-pollination while corresponding with European botanists to exchange specimens and gain access to non-native species in her corner of North America. Her descriptions integrated Linnaean taxonomy with careful notes on each plant’s morphology, habitat, and practical uses—many derived from local Indigenous knowledge—and were accompanied by her own finely detailed illustrations and nature prints. Her drawings are simplistic but charming in their linear detail, made using “china ink with a pencil”. Although her illustrations appear to us in monochrome, it’s said they were once coloured with neutral washes to accentuate the details.

Along with her vast catalogue of sketches, she produced 300 impressions of her specimens printed from nature. Nature Printing is an established printing technique that involves inking a natural specimen to make an impression print on paper. Developed in the Middle Ages, it is a method of documentation that pre-dates modern methods of scientific illustration and photography. Evolving into a serious practice to identify and permanently record plant species, nature printing captures the essence of the natural object, beautifully showcasing the frameworks and patterns that uphold the natural world.

America's first female botanist

Through her father’s extensive correspondence, Colden’s achievements became known to the transatlantic scientific community and eventually drew the attention of Linnaeus himself. Though her Flora of New York manuscript remained unpublished and her botanical studies ceased after her marriage in 1759, her beautifully illustrated body of work endures as a significant contribution to early American science.

In capturing the essence of eighteenth-century botany through the unexplored flora of colonial New York, Jane Colden emerged as both America’s first woman botanist and the earliest interpreter of the Linnaean system on its soil.

rEAD MORE ABOUT THE ART AND SCIENCE OF WOMEN IN BOTANY

sHOP THE ART MEETS SCIENCE COLLECTION

-

Art/Chemistry/Illustration/Japanese Woodblock/Pyrotechnics/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Chemistry/Illustration/Japanese Woodblock/Pyrotechnics/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageJinta Hirayama’s Japanese Firework Illustrations

£6.99 – £24.99Price range: £6.99 through £24.99 -

Nature/Botany/Illustration/Mushrooms/MycologySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Nature/Botany/Illustration/Mushrooms/MycologySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageAnna Maria Hussey’s Mushroom Illustrations

£7.99 – £29.99Price range: £7.99 through £29.99 -

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageMunsell’s Colour System

£7.99 – £25.99Price range: £7.99 through £25.99 -

Art/Astronomy/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Astronomy/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageUrania’s Star Charts

£7.99 – £29.99Price range: £7.99 through £29.99 -

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageEmily Vanderpoel’s Color Problems

£7.99 – £34.99Price range: £7.99 through £34.99 -

Animals/Butterflies & Moths/NatureSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Animals/Butterflies & Moths/NatureSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageMaria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis

£9.99 – £34.99Price range: £9.99 through £34.99