Elizabeth Blackwell’s Curious Herbal represents a landmark in eighteenth-century botanical illustration, natural science, and visual culture.

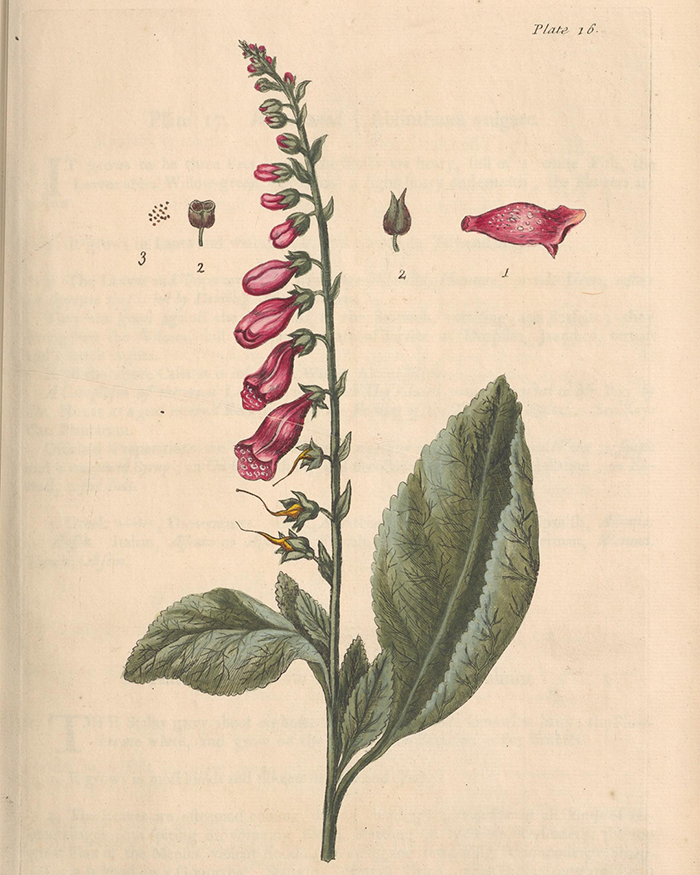

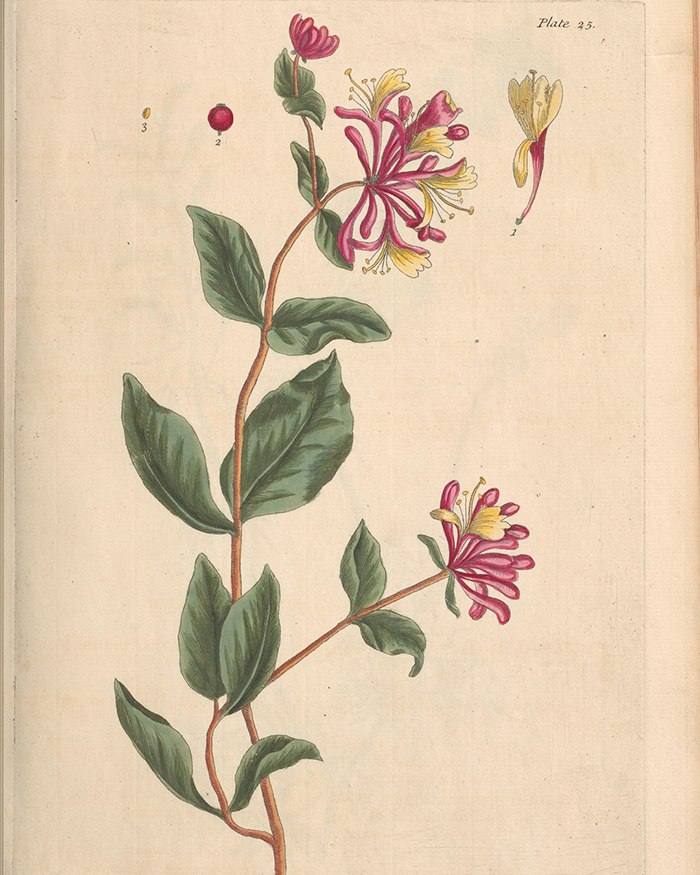

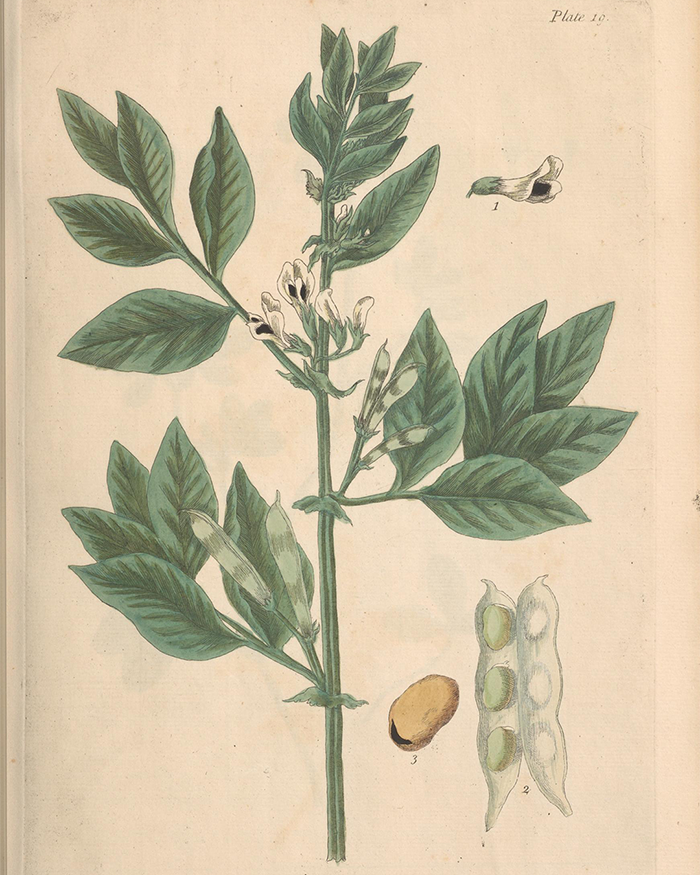

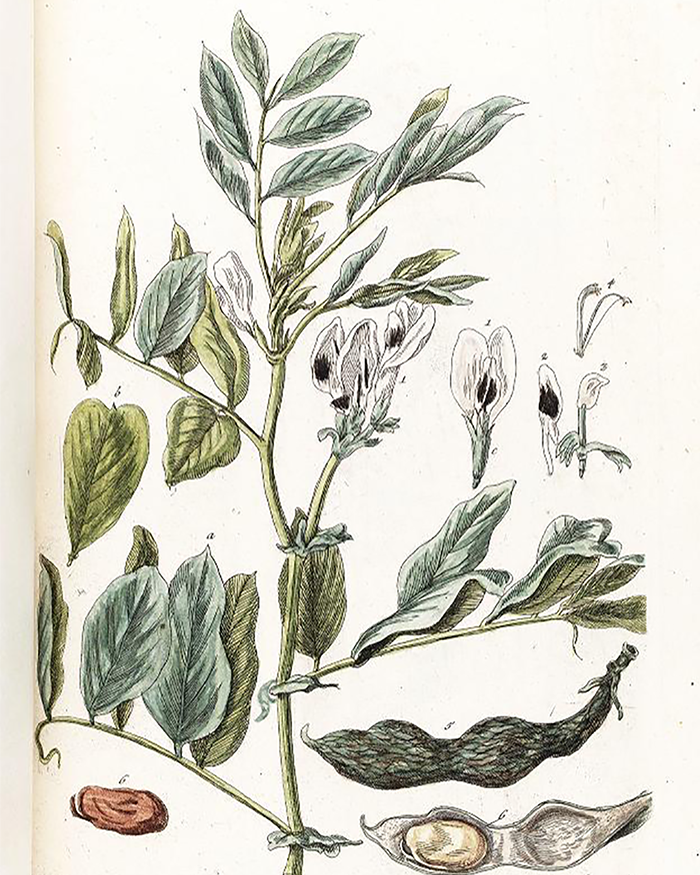

Trained as an artist in Aberdeen and evidently educated in aspects of medicine and herbal pharmacology, Blackwell (1707-1758) combined artistic precision with scientific understanding to produce one of the most authoritative herbals of her time. She worked from living specimens cultivated at the Chelsea Physic Garden, London, having taken convenient lodgings nearby, where she drew, engraved, and hand-coloured more than 500 plates herself. Her scientific illustrations showcased an exceptional level of authorship in early modern scientific publishing, and almost unprecedented for a woman of her period

The History of the Illustrated Herbal

Before the printed book, herbal wisdom was passed on by word of mouth, a tradition half magic and half medicine. When illustrations entered the herbal, the book’s character changed entirely, allowing plants to be studied for both their form and their virtues.

When its lore had become science, the eighteenth century saw the traditional herbal die of its own success. The new botanists, trained in Linnaeus’s method, no longer sought the virtues of herbs but their place in the system. Yet even in this transition period, a few noteworthy herbals appeared, among them Blackwell’s work.

From the first, herbal medicine had been a predominantly domestic practice, with herbal remedies and tinctures a form of kitchen magic to aid the sick. It is characteristic that the first herbal volume drawn from the living plant by a woman was intended to serve both the apothecary and the household practitioner.

“The work of this learned and ingenious lady surpassed all that had been

published… [a] valuable treasure of botanical knowledge.”

—Waterhouse, 1811

Women botanical illustrators

Published in weekly instalments between 1737 and 1739, A Curious Herbal provided physicians and apothecaries with an affordable, accurate reference that united visual and textual knowledge, detailing each plant’s morphology, flowering season, and medicinal properties. The work encompassed both local flora and newly introduced species from Asia, Africa, and the Americas, reflecting the expanding global networks of botanical exchange. It earned formal commendation from the Royal College of Physicians and praise from leading physicians and naturalists, including Sir Hans Sloane, Dr Richard Mead, and her close acquaintance Carl Linnaeus, who referred to her as Botanica Blackwellia.

Elizabeth Blackwell: BOtanist

Not to be confused with her later namesake, the pioneering physician Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910), our Elizabeth Blackwell was also knowledgeable in areas of medicine and pharmacology. Although it’s recorded that she first learnt midwifery to raise funds after her husband was fined for practising medicine without a proper license, Blackwell’s medical and botanical knowledge left her in good standing when compiling her herbal.

This complex background situates her instead as a learned and resourceful figure operating at the intersection of art and science, whose intellectual and practical expertise informed one of the most important botanical works of the eighteenth century:

Elizabeth Blackwell… was considered by James Douglas (1675-1742) to be one of the hundred most famous women of history. Douglas was himself famous as an obstetrician, surgeon, and anatomist… his friendship with Elizabeth Blackwell began in Scotland, where she lived with her husband, a physician named Alexander Blackwell, who was a graduate of Aberdeen University, a printer, and an apothecary.

Elizabeth studied botany and anatomy both with her husband and with Dr Douglas, becoming so proficient in flower painting and copper-plate engraving that, when her husband was imprisoned for debt in 1737, the earnings from her book paid his fines. When Alexander was again imprisoned, this time for conspiracy against the King of Sweden, she studied obstetrics with Smellie to support herself and soon became a popular and successful practitioner. She won the friendship and admiration of Sir Hans Sloane and the famous Dr Richard Mead, and like them had a large income.

Her husband was finally beheaded for treason, apologising at the last moment for not knowing just “where to lay his head on the block because it was his first experience,” after which tragedy, Elizabeth continued her obstetric as well as general practice until her death at the age of fifty-eight. Dr Elizabeth Blackwell of the nineteenth century regarded Elizabeth, her predecessor, as a type of “physician-accoucheur worthy of all praise.”

—Campbell Hurd-Mead, 1938

The Art and Science of Elizabeth Blackwell

The significance of A Curious Herbal extends beyond its immediate financial purpose. As an exquisitely produced volume of natural history illustrations, it provided the most comprehensive visual record of medicinal plants available in Britain at the time, preceding later works such as William Woodville’s Medical Botany (1790–95). Between 1747 and 1773, an expanded edition was published, Herbarium Blackwellianum, with redrawn plates by N. F. Eisenberger, extending the work into six volumes.

“The story of Mrs Elizabeth Blackwell is so remarkable as an instance of patient perseverance and quiet heroism… that she may fairly claim a place in the list of Scottish artists.”

—Brydall, 1889

Although profits from A Curious Herbal were used to secure the release of her husband, Alexander Blackwell (1700–1747), from debtor’s prison, this circumstance has long dominated her biographical narrative—often reducing her remarkable scientific and artistic achievement to an act of spousal devotion. In reality, Blackwell’s Herbal occupies a pivotal position in the history of botany, bridging pre-Linnaean descriptive traditions and the emerging taxonomic systems that would shape modern botanical science.

Her combination of medical knowledge, empirical observation, and artistic technique established a new model for the study and documentation of medicinal plants, securing her place as one of the foremost women in eighteenth-century natural history.

explore the art meets science collection

-

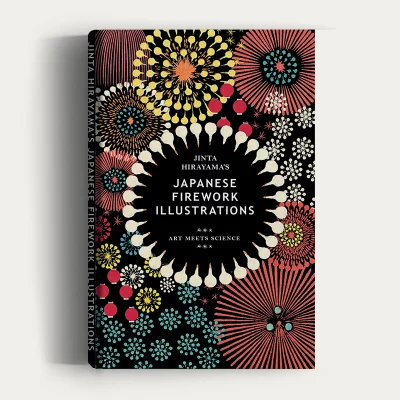

Art/Chemistry/Illustration/Japanese Woodblock/Pyrotechnics/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Chemistry/Illustration/Japanese Woodblock/Pyrotechnics/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageJinta Hirayama’s Japanese Firework Illustrations

£6.99 – £24.99Price range: £6.99 through £24.99 -

Nature/Botany/Illustration/Mushrooms/MycologySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Nature/Botany/Illustration/Mushrooms/MycologySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageAnna Maria Hussey’s Mushroom Illustrations

£7.99 – £29.99Price range: £7.99 through £29.99 -

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageMunsell’s Colour System

£7.99 – £25.99Price range: £7.99 through £25.99 -

Art/Astronomy/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Astronomy/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageUrania’s Star Charts

£7.99 – £29.99Price range: £7.99 through £29.99 -

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Art/Color TheorySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageEmily Vanderpoel’s Color Problems

£7.99 – £34.99Price range: £7.99 through £34.99 -

Animals/Butterflies & Moths/NatureSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Animals/Butterflies & Moths/NatureSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageMaria Sibylla Merian’s Metamorphosis

£9.99 – £34.99Price range: £9.99 through £34.99 -

Human Anatomy & Physiology/Life Sciences/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Human Anatomy & Physiology/Life Sciences/ScienceSelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageHenry Gray’s Anatomy

£9.99 – £39.99Price range: £9.99 through £39.99 -

Artists' Books/Individual Photographers/PhotographySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Artists' Books/Individual Photographers/PhotographySelect options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageAnna Atkins’ Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns

£9.99 – £24.99Price range: £9.99 through £24.99